In my humble opinion, the story of St. Patrick is a story of a lost opportunity for the modern church. It begins like this…

In my humble opinion, the story of St. Patrick is a story of a lost opportunity for the modern church. It begins like this…

1 I, Patrick, a sinner, a most simple countryman, the least of all the faithful and most contemptible to many, had for father the deacon Calpurnius, son of the late Potitus, a priest, of the settlement [vicus] of Bannavem Taburniae; he had a small villa nearby where I was taken captive. I was at that time about sixteen years of age. I did not, indeed, know the true God; and I was taken into captivity in Ireland with many thousands of people, according to our desserts, for quite drawn away from God, we did not keep his precepts, nor were we obedient to our priests who used to remind us of our salvation. And the Lord brought down on us the fury of his being and scattered us among many nations, even to the ends of the earth, where I, in my smallness, am now to be found among foreigners.

2 And there the Lord opened my mind to an awareness of my unbelief, in order that, even so late, I might remember my transgressions and turn with all my heart to the Lord my God, who had regard for my insignificance and pitied my youth and ignorance. And he watched over me before I knew him, and before I learned sense or even distinguished between good and evil, and he protected me, and consoled me as a father would his son.

3 Therefore, indeed, I cannot keep silent, nor would it be proper, so many favours and graces has the Lord deigned to bestow on me in the land of my captivity. For after chastisement from God, and recognizing him, our way to repay him is to exalt him and confess his wonders before every nation under heaven.

Source: The “Confessio” of St. Patrick –

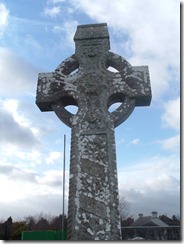

You can go to the source and read the rest of his story if you are so inclined. In this post, however, I’d like to focus on this image…

In my humble opinion, pastors would do well to study the history of St. Patrick and learn from him while the church would also benefit from taking advantage of the only ‘national holiday’ that honors one of the greatest evangelists of all time even if parts of Patrick are only a legend. The History Channel gives us some insight as to Patrick’s tactics…

Familiar with the Irish language and culture, Patrick chose to incorporate traditional ritual into his lessons of Christianity instead of attempting to eradicate native Irish beliefs. For instance, he used bonfires to celebrate Easter since the Irish were used to honoring their gods with fire. He also superimposed a sun, a powerful Irish symbol, onto the Christian cross to create what is now called a Celtic cross, so that veneration of the symbol would seem more natural to the Irish. Although there were a small number of Christians on the island when Patrick arrived, most Irish practiced a nature-based pagan religion. The Irish culture centered around a rich tradition of oral legend and myth. When this is considered, it is no surprise that the story of Patrick’s life became exaggerated over the centuries—spinning exciting tales to remember history has always been a part of the Irish way of life.

Source: Who Was St. Patrick? — History.com Articles, Video, Pictures and Facts

PBS takes a more skeptical view of Patrick in their documentary “In search of ancient Ireland”…

During the final period before the coming of Christianity to Ireland in the 5th century A.D., religion in Ireland was still concerned with the forces of nature so important to farming populations. Druids were the priests or soothsayers of this Celtic world, intermediaries between human existence and the Otherworld.

Stories written down centuries later by Christian monks provide clues to this Celtic religion, as do descriptions by Roman writers who witnessed European Celtic rituals. Human sacrifice existed, but only in times of great need. Worship was more celebrational than liturgical, with people gathering on the Quarter Days — February 1 (Imbolg), May 1 (Beltine), August 1 (Lunasa), and November 1 (Samain, our Halloween) — to celebrate the cycle of the seasons. Rome’s conquest of most of Europe, and later adoption of Christianity, suppressed such Celtic rituals, but in Ireland, beyond Rome’s influence, the old religion continued.

Christian missionaries like Patrick arrived in Ireland in the 5th century A.D., settling close to royal centers of power and targeting local kings and their families. Conversion was a piecemeal operation, but Christianity spread from the top down. Missionaries like Patrick understood that much of the sophisticated religious system already in place fitted in with Christianity. There was convergence and accommodation as many pagan practices were absorbed into the Celtic Irish church, making the new religion easier to accept. Compared to Christianity’s spread elsewhere, conversion was gradual and non-violent.

Legends portray Patrick as the primary force behind Ireland’s peaceful conversion, but he was one of many early missionaries, unimportant in his own lifetime. A century after his death, the monastery in Armagh — supposedly founded by Patrick — began its campaign to dominate the Irish church. As its power grew, so too did the cult of its founder. Christianity’s spread across Ireland was accelerated in the 6th century by climate disaster and plague, the result, according to church leaders, of pagan wickedness. Since writing only came to Ireland with Christianity, the church also controlled literacy and thus the primary means of education.

Slate spins it this way…

The Irish have celebrated their patron saint with a quiet religious holiday for centuries, perhaps more than 1,000 years. It took the United States to turn St. Patrick’s Day into a boozy spectacle. Irish immigrants first celebrated it in Boston in 1737 and first paraded in New York in 1762. By the late 19th century, the St. Patrick’s Day parade had become a way for Irish-Americans to flaunt their numerical and political might. It retains this role today.

The scarcity of facts about St. Patrick’s life has made him a dress-up doll: Anyone can create his own St. Patrick. Ireland’s Catholics and Protestants, who have long feuded over him, each have built a St. Patrick in their own image. Catholics cherish Paddy as the father of Catholic Ireland. They say that Patrick was consecrated as a bishop and that the pope himself sent him to convert the heathen Irish. (Evidence is sketchy about both the bishop and pope claims.) One of the most popular Irish Catholic stories holds that Patrick bargained with God and got the Big Fella to promise that Ireland would remain Catholic and free.

Ireland’s Protestant minority, by contrast, denies that Patrick was a bishop or that he was sent by Rome. They depict him as anti-Roman Catholic and credit him with inventing a distinctly Celtic church, with its own homegrown symbols and practices. He is an Irish hero, not a Catholic one.

Outside Ireland, too, Patrick has been freely reinterpreted. Evangelical Protestants claim him as one of their own. After all, he read his Bible, and his faith came to him in visions. Biblical inspiration and personal revelation are Protestant hallmarks. Utah newspapers emphasize that Patrick was a missionary sent overseas to convert the ungodly, an image that resonates in Mormon country. New Age Christians revere Patrick as a virtual patron saint. Patrick co-opted Druid symbols in order to undermine the rival religion, fusing nature and magic with Christian practice. The Irish placed a sun at the center of their cross. “St. Patrick’s Breastplate,” Patrick’s famous prayer (which he certainly did not write) invokes the power of the sun, moon, rocks, and wind, as well as God. (This is what is called “Erin go hoo-ha.”)

Patrick has even been enlisted in the gay rights cause. For a decade, gay and lesbian Irish-Americans have sought permission to march in New York’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade, and for a decade they have lost in court. Cahill, among others, has allied Patrick with gays and lesbians. Cahill’s Patrick is a muscular progressive. He was a proto-feminist who valued women in an age when the church ignored them. He always sided with the downtrodden and the excluded, whether they were slaves or the pagan Irish. If Patrick were around today, Cahill says, he would join the gay marchers.

Source: St. Patrick: No snakes. No shamrocks. Just the facts. – Slate Magazine

The ‘truth’, I suspect, is somewhere in between but there are lessons from Patrick’s tactics — tactics that resulted in the only conversion of an entire country to Christianity without martyrdom — that may be lost on the modern church…

- The story of Patrick is the story of a man who overcame great adversity to preach the faith…

- Patrick used the symbols and ‘media’ of his time to connect and convert…

- His legacy and the legacy of other Irish missionaries and saintly scholars have changed the course of history [Do you doubt? Read “How the Irish Saved Civilization“]…

The conversion of Poland, for example, and the ascendancy of John Paul II was as a result of a single Irish missionary following the call to Poland but I have yet to hear a sermon on the lessons of St. Patrick for modern man. For me this represents a lost opportunity to ‘take back’ the only holiday that honors evangelism and an evangelist, however nebulous that story may be but sorting out the man from the myth would be one of the best parts!