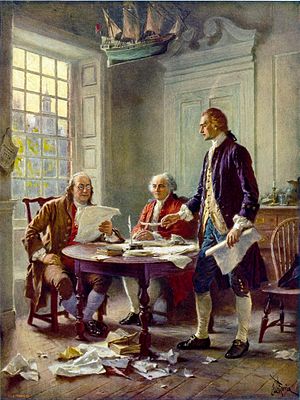

“The Second Day of July 1776 will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires, and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.” – John Adams to Abigail Adams, July 3, 1776. 1776 filled the calendar with dates deserving of remembrance and even celebration. John Adams, delegate from Massachusetts to the Second Continental Congress, wrote home to his wife Abigail that future generations would celebrate July 2, the date the Congress voted to approve Richard Henry Lee’s resolution declaring independence from Britain for 13 of the British colonies in America. Two days later, that same Congress approved the wording of the document Thomas Jefferson had drafted to announce Lee’s resolution to the world. Today, we celebrate the date of the document Jefferson wrote, and Richard Henry Lee is often a reduced to a footnote, if not erased from history altogether. Who can predict the future? (You know, of course, that Adams and Jefferson both died 50 years to the day after the Declaration of Independence, on July 4, 1826. In the 50 intervening years, Adams and Jefferson were comrades in arms and diplomacy in Europe, officers of the new government in America, opposing candidates for the presidency, President and Vice President, ex-President and President, bitter enemies, then long-distance friends writing almost daily about how to make a great new nation. Read David McCullough’s version of the story, if you can find it.)”

You must be logged in to post a comment.