The first six months of the Revolution saw the Continental Army chased out of New York, across New Jersey, and into Pennsylvania.

Ranks dwindled from 20,000 to 2,000 exhausted soldiers- most leaving at year’s end when their six-month enlistment was up.

Expecting a British invasion, the Continental Congress fled Philadelphia and sent the word:

“Until Congress shall otherwise order, General Washington shall be possessed of full power to order and direct all things.”

In a military operation, with the password “Victory or Death,” Washington’s troops crossed the ice-filled Delaware River at midnight Christmas Day.

Trudging in a blinding blizzard, with one soldier freezing to death, they attacked the feared Hessian troops at Trenton, New Jersey, on daybreak DECEMBER 26, 1776, capturing nearly a thousand in just over an hour.

A few Americans were shot and wounded, including James Monroe, the future 5th President.

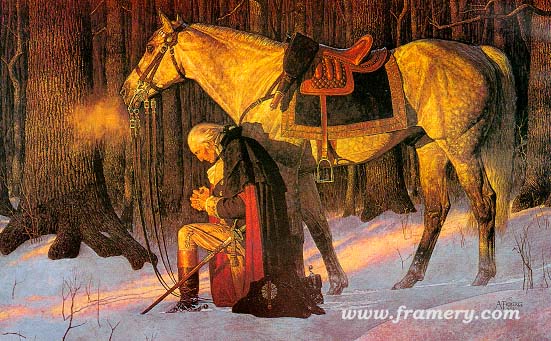

Washington wrote August 20, 1778:

“The Hand of Providence has been so conspicuous in all this-the course of the war-that he must be worse than an infidel that lacks faith, and more wicked that has not gratitude to acknowledge his obligations; but it will be time enough for me to turn Preacher when my present appointment ceases.”

George Washington assigned to lead the Continental Army; This Day in History

On this day in 1775, George Washington, who would one day become the first American president, accepts an assignment to lead the Continental Army.

Washington had been managing his family’s plantation and serving in the Virginia House of Burgesses when the second Continental Congress unanimously voted to have him lead the revolutionary army. He had earlier distinguished himself, in the eyes of his contemporaries, as a commander for the British army in the French and Indian War of 1754.

Born a British citizen and a former Redcoat, Washington had, by the 1770s, joined the growing ranks of colonists who were dismayed by what they considered to be Britain’s exploitative policies in North America. In 1774, Washington joined the Continental Congress as a delegate from Virginia. The next year, the Congress offered Washington the role of commander in chief of the Continental Army.

After accepting the position, Washington sat down and wrote a letter to his wife, Martha, in which he revealed his concerns about his new role. He admitted to his “dear Patcy” that he had not sought the post but felt “it was utterly out of my power to refuse this appointment without exposing my Character to such censures as would have reflected dishonour upon myself, and given pain to my friends.” He expressed uneasiness at leaving her alone, told her he had updated his will and hoped that he would be home by the fall. He closed the letter with a postscript, saying he had found some of “the prettiest muslin” but did not indicate whether it was intended for her or for himself.

On July 3, 1775, Washington officially took command of the poorly trained and under-supplied Continental Army. After six years of struggle and despite frequent setbacks, Washington managed to lead the army to key victories and Great Britain eventually surrendered in 1781. Due largely to his military fame and humble personality, Americans overwhelmingly elected Washington their first president in 1789.

Continental Congress chooses national flag; This Day in History

On this day in 1777, during the American Revolution, the Continental Congress adopts a resolution stating that “the flag of the United States be thirteen alternate stripes red and white” and that “the Union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation.”

The national flag, which became known as the “stars and stripes,” was based on the “Grand Union” flag, a banner carried by the Continental Army in 1776 that also consisted of 13 red and white stripes. According to legend, Philadelphia seamstress Betsy Ross designed the new canton for the flag, which consisted of a circle of 13 stars and a blue background, at the request of General George Washington. Historians have been unable to conclusively prove or disprove this legend.

With the entrance of new states into the United States after independence, new stripes and stars were added to represent new additions to the Union. In 1818, however, Congress enacted a law stipulating that the 13 original stripes be restored and that only stars be added to represent new states.

On June 14, 1877, the first Flag Day observance was held on the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the American flag. As instructed by Congress, the U.S. flag was flown from all public buildings across the country. In the years after the first Flag Day, several states continued to observe the anniversary, and in 1949 Congress officially designated June 14 as Flag Day, a national day of observance.” via Continental Congress chooses national flag — History.com This Day in History — 6/14/1777.

Why July 4th is NOT exactly the day of US Independence

Historically, the legal liberation of 13 original colonies took place on July 2, 1776, in a closed session of Congress. However, the Second Continental Congress took two more days to modify the famous of American documents, delaying the final approval of Declaration of Independence by two more days.

Although the Declaration of Independence managed to get the Congressional approval on July 4, 1776, it was not made public until July 8. Thus the first Independence Day was celebrated on July 8, 1776.

The Declaration of Independence was read on July 8th, 1776 by Col. John Nixon. He, less than a year later, would be made a brigadier general of the Continental Army.

The day saw summoning of citizens to Independence Hall for the very first public reading of the US Independence Declaration, by ringing the bells of Philadelphia, including the Liberty Bell. This breaks yet another American myth regarding the ringing of Liberty Bell.

Contrary to the popular misconception, Liberty Bell did not ring on July 4th, 1776 to mark the US Independence day. Americans had to wait four more days, till July 8th, to listen to the Liberty Bell as well as the public reading of Declaration of Independence.

My birthday falls on July 8th which would appear is the best of all American holidays according to historical fact…

You must be logged in to post a comment.