Does your Weltanschauung need an upgrade? I’ve got you.

The Good, the Bad, and the Technology

Embracing the coexistence of “good and bad” is essential for authentic progress. Here’s an excerpt:

“Philosophers like Friedrich Nietzsche and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel have deeply explored the concept of duality. Nietzsche’s idea of “eternal recurrence” posits that life is a repetitive cycle of events that includes both triumphs and tragedies. Hegel’s dialectic underlines that the synthesis of thesis and antithesis results in a higher form of understanding. In both instances, the existence of bad is not merely an unfortunate byproduct of reality but an essential catalyst for growth and progress.”

I’m predisposed to like any author or article that positively uses Hegel’s dialectic. Just sayin’ :-D

And I did rise…

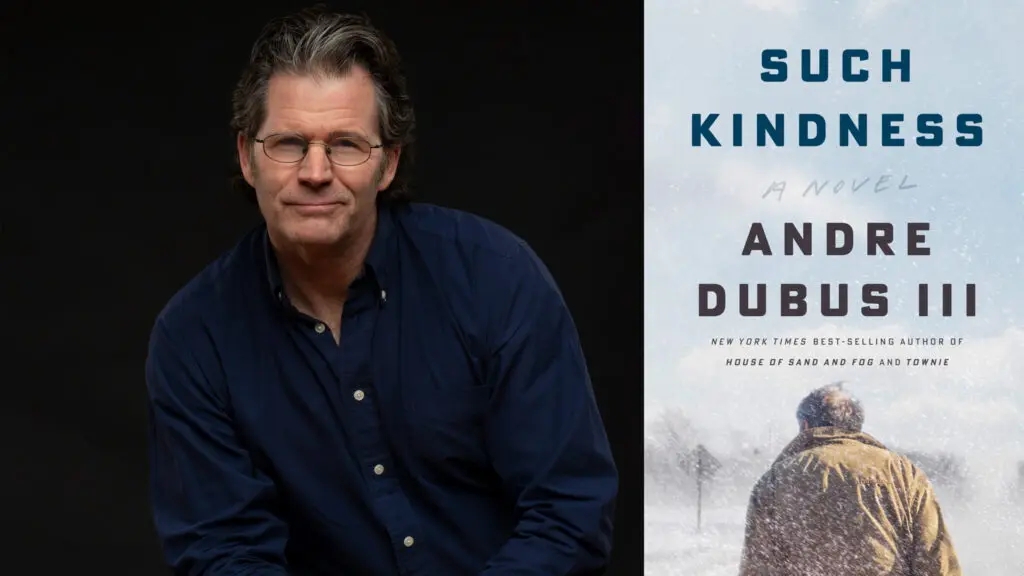

How can I not reblog this? Hesse’s Siddhartha literally changed the trajectory of my life. My master’s thesis was on the connection between Hesse’s Siddhartha and Hegel’s Dialectic. Had I continued on with my doctoral degree my goal would have been to become a world famous Hermann Hesse scholar. Search this brightshinyobjects.net for the words Hesse and/or Siddhartha and/or dialectic and you’ll see that my passion for this topic still smolders beneath the surface. If you haven’t read Siddhartha you owe it to yourself. It’s a book I have read every year for the past 45 years…

(He) handed me a copy of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. “In the shade of the house, in the sunshine of the riverbank near the boats, in the shade of the Sal-wood forest, in the shade of the fig tree is where Siddhartha grew up.” Reading that sentence for the first time in the small bedroom I shared with Charlie, it was as if I were reading about myself: In the shade of the house, in the sunshine of the highway near the droning automobiles, in the shade of the pine trees, in the shade of the dead-end street is where Tom Lowe Jr. grew up. Siddhartha and his search for who he was meant to be, it was me on that river, it was me on those banks, and it was me who began to see books as doorways to worlds that could only help me rise in this…

View original post 232 more words

What is the connection between Hermann Hesse and Hegel’s Dialectic?

There is a connection between Hermann Hesse’s work and Hegel’s dialectic in the sense that Hesse was influenced by Hegelian philosophy and dialectical thinking, and this influence can be seen in Hesse’s novels, particularly in his exploration of themes such as self-discovery and personal transformation.

Hegelian dialectic is a philosophical concept that involves the resolution of opposing ideas or contradictions through a process of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. This process of dialectical thinking involves the transformation of ideas and the search for a higher truth or resolution.

In Hesse’s novels, such as “Demian” and “Steppenwolf,” we see a similar exploration of opposing ideas and the search for a higher truth. Hesse’s characters often undergo a process of transformation, struggling with their own contradictions and ultimately finding a synthesis or resolution through their experiences.

Continue reading “What is the connection between Hermann Hesse and Hegel’s Dialectic?”Uh oh?

Speaking of progress — as I was in my previous post — it’s not continuous! In face, September — as I adjusted to a new schedule with school back in session, etc., was my either my 4th best or my 3rd worst [depending on your perspective] since I started exercising again…

Am I worried about ‘losing it’? Not in the least. I’m learning to practice moderation and consistency and adjusting to changing weather. More important is that overall I am making progress. According to Endomondo, I’ve exercised 83% of the days since I started in March — that’s a low B in just about anybody’s book…

The most important thing is that exercise is now an important part of my life again and I’m making progress. Dialectical progress, but progress nonetheless…

Dialectical progress…

Looking back at this past week and trying to understand the lessons the Universe has for me is ‘progress’ and in particular I’m thinking about the dialectical nature of progress. Dialectical? I’ll have more on that later. First, here are the two posts that got me thinking. The first, an excellent lesson from Christine Hassler on why change or progress is not linear called ‘Ever Feel Like You’re backtracking?. I read another good one one from Jason Wachob earlier this week called Forget Perfection: Strive Toward Progress. There are other good ones I’ve curated as well — just search for ‘progress’ or ‘perfection’ in the search bar…

These posts made me think about my incomplete doctoral thesis on the relationship between Hermann Hesse’s writings and Hegel’s Dialectic. What is Hegel’s Dialectic? Here’s the wikipedia definition:

“Hegelian dialectic, usually presented in a threefold manner, was stated by Heinrich Moritz Chalybäus as comprising three dialectical stages of development: a thesis, giving rise to its reaction, an antithesis, which contradicts or negates the thesis, and the tension between the two being resolved by means of a synthesis. Although this model is often named after Hegel, he himself never used that specific formulation. Hegel ascribed that terminology to Kant.[28] Carrying on Kant’s work, Fichte greatly elaborated on the synthesis model, and popularized it.

On the other hand, Hegel did use a three-valued logical model that is very similar to the antithesis model, but Hegel’s most usual terms were: Abstract-Negative-Concrete. Hegel used this writing model as a backbone to accompany his points in many of his works.

The formula, thesis-antithesis-synthesis, does not explain why the thesis requires an Antithesis. However, the formula, abstract-negative-concrete, suggests a flaw, or perhaps an incomplete-ness, in any initial thesis—it is too abstract and lacks the negative of trial, error and experience. For Hegel, the concrete, the synthesis, the absolute, must always pass through the phase of the negative, in the journey to completion, that is, mediation. This is the actual essence of what is popularly called Hegelian Dialectics.

To describe the activity of overcoming the negative, Hegel also often used the term Aufhebung, variously translated into English as “sublation” or “overcoming,” to conceive of the working of the dialectic. Roughly, the term indicates preserving the useful portion of an idea, thing, society, etc., while moving beyond its limitations. (Jacques Derrida’s preferred French translation of the term was relever).[29]

In the Logic, for instance, Hegel describes a dialectic of existence: first, existence must be posited as pure Being (Sein); but pure Being, upon examination, is found to be indistinguishable from Nothing (Nichts). When it is realized that what is coming into being is, at the same time, also returning to nothing (in life, for example, one’s living is also a dying), both Being and Nothing are united as Becoming.[30]

As in the Socratic dialectic, Hegel claimed to proceed by making implicit contradictions explicit: each stage of the process is the product of contradictions inherent or implicit in the preceding stage. For Hegel, the whole of history is one tremendous dialectic, major stages of which chart a progression from self-alienation as slavery to self-unification and realization as the rational, constitutional state of free and equal citizens. The Hegelian dialectic cannot be mechanically applied for any chosen thesis. Critics argue that the selection of any antithesis, other than the logical negation of the thesis, is subjective. Then, if the logical negation is used as the antithesis, there is no rigorous way to derive a synthesis. In practice, when an antithesis is selected to suit the user’s subjective purpose, the resulting “contradictions” are rhetorical, not logical, and the resulting synthesis is not rigorously defensible against a multitude of other possible syntheses. The problem with the Fichtean “Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis” model is that it implies that contradictions or negations come from outside of things. Hegel’s point is that they are inherent in and internal to things. This conception of dialectics derives ultimately from Heraclitus.” Full story at: Dialectic – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.”

Pretty heady stuff, eh? Basically, it’s just another way of describing that ‘two steps forward one step back’ process we call progress. Wherever you’re at as you read this, stop, look yourself in the mirror and say “I’m enough and I’ve come as far as I can”. Remember, your best days are still ahead…

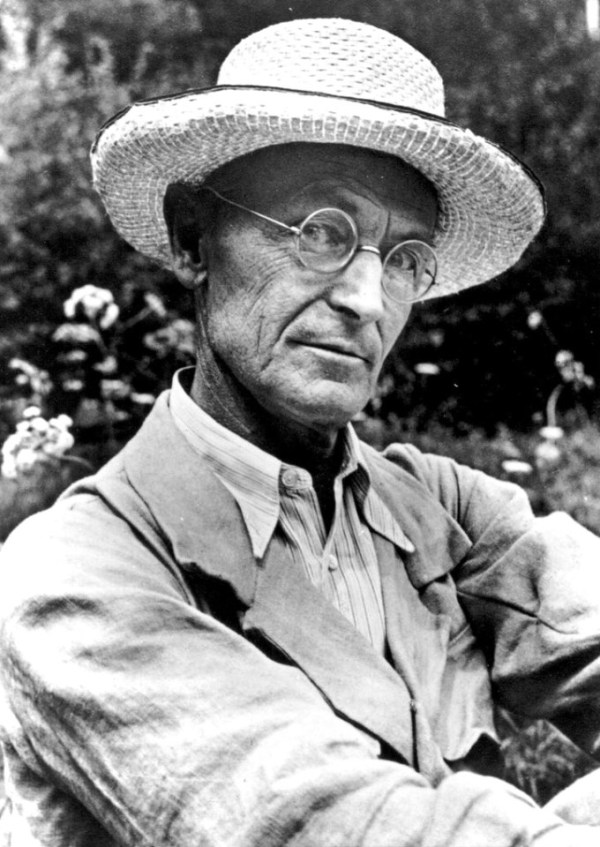

Happy birthday, Hermann Hesse!

I was born in Calw in the Black Forest on July 2, 1877. My father, a Baltic German, came from Estonia; my mother was the daughter of a Swabian and a French Swiss. My father’s father was a doctor, my mother’s father a missionary and Indologist. My father, too, had been a missionary in India for a short while, and my mother had spent several years of her youth in India and had done missionary work there.My childhood in Calw was interrupted by several years of living in Basle (1880-86). My family had been composed of different nationalities; to this was now added the experience of growing up among two different peoples, in two countries with their different dialects.

I spent most of my school years in boarding schools in Wuerttemberg and some time in the theological seminary of the monastery at Maulbronn. I was a good learner, good at Latin though only fair at Greek, but I was not a very manageable boy, and it was only with difficulty that I fitted into the framework of a pietist education that aimed at subduing and breaking the individual personality. From the age of twelve I wanted to be a poet, and since there was no normal or official road, I had a hard time deciding what to do after leaving school. I left the seminary and grammar school, became an apprentice to a mechanic, and at the age of nineteen I worked in book and antique shops in Tübingen and Basle. Late in 1899 a tiny volume of my poems appeared in print, followed by other small publications that remained equally unnoticed, until in 1904 the novel Peter Camenzind, written in Basle and set in Switzerland, had a quick success. I gave up selling books, married a woman from Basle, the mother of my sons, and moved to the country. At that time a rural life, far from the cities and civilization, was my aim. Since then I have always lived in the country, first, until 1912, in Gaienhofen on Lake Constance, later near Bern, and finally in Montagnola near Lugano, where I am still living.

Soon after I settled in Switzerland in 1912, the First World War broke out, and each year brought me more and more into conflict with German nationalism; ever since my first shy protests against mass suggestion and violence I have been exposed to continuous attacks and floods of abusive letters from Germany. The hatred of the official Germany, culminating under Hitler, was compensated for by the following I won among the young generation that thought in international and pacifist terms, by the friendship of Romain Rolland, which lasted until his death, as well as by the sympathy of men who thought like me even in countries as remote as India and Japan. In Germany I have been acknowledged again since the fall of Hitler, but my works, partly suppressed by the Nazis and partly destroyed by the war; have not yet been republished there.

In 1923, I resigned German and acquired Swiss citizenship. After the dissolution of my first marriage I lived alone for many years, then I married again. Faithful friends have put a house in Montagnola at my disposal.

Until 1914 I loved to travel; I often went to Italy and once spent a few months in India. Since then I have almost entirely abandoned travelling, and I have not been outside of Switzerland for over ten years.

I survived the years of the Hitler regime and the Second World War through the eleven years of work that I spent on the Glasperlenspiel (1943) [Magister Ludi], a novel in two volumes. Since the completion of that long book, an eye disease and increasing sicknesses of old age have prevented me from engaging in larger projects.

Of the Western philosophers, I have been influenced most by Plato, Spinoza, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche as well as the historian Jacob Burckhardt. But they did not influence me as much as Indian and, later, Chinese philosophy. I have always been on familiar and friendly terms with the fine arts, but my relationship to music has been more intimate and fruitful. It is found in most of my writings. My most characteristic books in my view are the poems (collected edition, Zürich, 1942), the stories Knulp (1915), Demian (1919), Siddhartha (1922), Der Steppenwolf (1927) [Steppenwolf], Narziss und Goldmund. (1930), Die Morgenlandfahrt (1932) [The Journey to the East], and Das Glasperlenspiel (1943) [Magister Ludi]. The volume Gedenkblätter (1937, enlarged ed. 1962) [Reminiscences] contains a good many autobiographical things. My essays on political topics have recently been published in Zürich under the title Krieg und Frieden (1946) [War and Peace].

I ask you, gentlemen, to be contented with this very sketchy outline; the state of my health does not permit me to be more comprehensive.” via nobelprize.org

Happy birthday, Hermann! You made a profound impact on my life through your body of work…

Related articles

- Hermann Hesse (edgeacuity.wordpress.com)

- My Weekend with Hermann Hesse (practicallytwisted.wordpress.com)

Splitting

Splitting creates instability in relationships, because one person can be viewed as either personified virtue or personified vice at different times, depending on whether he or she gratifies the subject’s needs or frustrates them. This along with similar oscillations in the experience and appraisal of the self lead to chaotic and unstable relationship patterns, identity diffusion, and Other-directed mood swings. Consequently, the therapeutic process can be greatly impeded by these oscillations, because the therapist too can become the target of splitting. To overcome the negative effects on treatment outcome, constant interpretations by the therapist are needed.[1]

Splitting contributes to unstable relationships and intense emotional experiences, something that has been noted especially with narcissists. Alexander Abdennur writes in his book on narcissistic personality disorder, Camouflaged Aggression, that “[t]hrough this splitting mechanism, the narcissist can suddenly and radically shift his allegiance. A trusted friend can become an enemy; the partner may become an adversary.”[2]

Treatment strategies have been developed for individuals and groups based on dialectical behavior therapy, and for couples.[3] There are also self help books on related topics such as mindfulness and emotional regulation that have been helpful for individuals who struggle with the consequences of splitting.[4]” Get more here: Splitting (psychology) – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Related articles

- Bipolar or Narcissistic Personality Disorder? (everydayhealth.com)

- Narcissism is its Own Dark Tale (krackedkillers.wordpress.com)

- Be Assertive When Divorcing High Conflict Partners (psychologytoday.com)

- Criticizing a narcissist (liturgical.wordpress.com)

- Narcissistic personality disorder – PubMed Health (tazromagna.wordpress.com)

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder (allaboutcounseling.com)

- Narcissists: “Enough About Me: Let’s Talk About Myself” (psychologytoday.com)

You must be logged in to post a comment.